Two complementary goals to leave no one behind

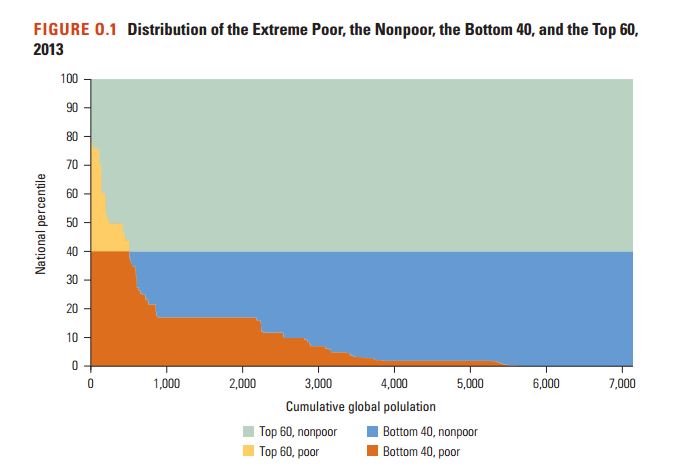

On April 20, 2013, the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank adopted two ambitious goals: end global extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity in every country in a sustainable way. This implies reducing the poverty headcount ratio from 10.7 percent globally in 2013 to 3.0 percent by 2030 and fostering the growth in the income or the consumption expenditure of the poorest 40 percent of the population (the bottom 40) in each country. These two goals are part of a wider international development agenda and are intimately related to United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals 1 and 10, respectively, which have been adopted by the global community. Each goal has an intrinsic value on its own merits, but the two goals are also highly complementary. Take the example of a low-income Sub-Saharan African country with a high poverty headcount ratio and an upper-middle-income country in Eastern Europe or Latin America with low levels of extreme poverty, but rising concerns about inequality. Ending extreme poverty is especially relevant in the former, while expanding shared prosperity is especially meaningful in the latter. The complementarity of the two goals also derives from the composition of the world’s poor and bottom 40 populations. At a global scale, while 9 in every 10 of the extreme poor were among the national bottom 40 in 2013, only a quarter of the bottom 40 were among the extreme poor (both cases refer to the orange area in figure O.1)

This complementarity has three important implications. First, by choosing these two goals, the World Bank focuses squarely on improving the welfare of the least well off across the world, effectively ensuring that everyone is part of a dynamic and inclusive growth process, no matter the circumstances, the country context, or the time period. Second, monitoring the two goals separately is necessary to understand with precision the progress in achieving better living conditions among those most in need. Third, policy interventions that reduce extreme poverty may or may not be effective in boosting shared prosperity if the two groups—the poor and the bottom 40— are composed of distinct populations. To understand more clearly the progress toward the achievement of the goals, the World Bank is launching the annual Poverty and Shared Prosperity report series, which this report inaugurates. The report series will inform a global audience comprising development practitioners, policy makers, researchers, advocates, and citizens in general with the latest and most accurate estimates on trends in global poverty and shared prosperity. Every year, it will update information on the global number of the poor, the poverty headcount ratio worldwide, the regions that have been more successful or that have been lagging in advancing toward the goals, and the enhancements in monitoring and measuring poverty. In addition, it will feature a special

Source: Inspired by Beegle et al. 2014 and updated with 2013 data. Note: The figure has been constructed from vertical bars representing countries sorted in descending order by extreme poverty headcount ratio (from left to right). The width of each bar reflects the size of the national population. The figure thus illustrates the situation across the total global population.

Inequality matters for achieving the goals, but also for other reasons

Despite decades of substantial progress in boosting prosperity and reducing poverty, the world continues to suffer from substantial inequalities. For example, the poorest children are four times less likely than the richest children to be enrolled in primary education across developing countries. Among the estimated 780 million illiterate adults worldwide, nearly two-thirds are women. Poor people face higher risks of malnutrition and death in childhood and lower odds of receiving key health care interventions.1 Such inequalities are associated with high financial cost, affect economic growth, and generate social and political burdens and barriers. But leveling the playing field is also an issue of fairness and justice that resonates across societies on its own merits.

These substantive considerations highlight the importance of directing attention to the problem of inequality. There are other reasons too. Sustaining the rapid progress in reducing poverty and boosting shared prosperity that has been achieved over the last 25 years is at risk because of the struggles across economies to recover from the global financial crisis that started in 2008 and the subsequent slowdown in global growth. The goal of eliminating extreme poverty by 2030—which is likely to become more difficult as we approach more closely to it—might not be achieved without accelerated economic growth or reductions in within-country inequalities, especially among those countries with large concentrations of the poor. Generally speaking, poverty can be reduced through higher average growth, a narrowing in inequality, or a combination of the two.2 Achieving the same poverty reduction during a slowdown in growth therefore requires a more equal income distribution. It follows that, to reach the goals, efforts to foster growth need to be complemented by equity-enhancing policies and interventions. Some level of inequality is desirable to maintain an appropriate incentive structure in the economy or simply because inequality also reflects different levels of talent and effort among individuals. However, the substantial inequality observed in the world today offers ample room for taking on inequality. Doing so without compromising growth is not only possible, but can be beneficial for poverty reduction and shared prosperity if done smartly. A trade-off between efficiency and equity is not inevitable. The evidence that equityenhancing interventions can also bolster economic growth and long-term prosperity is wide-ranging. To the extent that such interventions interrupt the intergenerational reproduction of inequalities of opportunity, they address the roots and drivers of inequality, while laying the foundations for boosting shared prosperity and fostering long-term growth. Reducing inequalities of opportunity among individuals, economies, and regions may also be conducive to political and societal stability and social cohesion. In more cohesive societies, threats arising from extremism, political turmoil, and institutional fragility are less likely.

The key question the report addresses: what can be done to take on inequality?

This report addresses the issue of inequality by documenting trends in inequality, identifying recent country experiences in successfully reducing inequality and boosting shared prosperity, examining key lessons, and synthesizing the evidence on public policies that lessen inequality by reducing poverty and promoting shared prosperity. Inequality exists in many dimensions, and the question “inequality of what?” is essential. The report focuses on inequalities in income or consumption expenditures, but it also analyzes the deprivations among the extreme poor and the well-being of the bottom 40. However, it does not address all types of inequality, for example, inequality related to ownership of assets. This does not mean that such forms of inequality do not deserve attention. According to Oxfam, 62 individuals in 2015 had the same wealth as the bottom half of the world’s population; within the African continent, this statistic is even more extreme.3 However, the report looks into inequality in income, in outcomes such as in health care and education, and inequality in opportunities. Income inequality and unequal opportunities are intimately related. This report aims to dispel myths around income inequality. Reflecting on what has worked in addressing this profound problem is key to taking on inequality more successfully. The report makes four main contributions. First, it presents the most recent numbers on poverty, shared prosperity, and inequality. Second, it stresses the importance of inequality reduction in ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity by 2030, particularly in a context of weaker growth. Third, it highlights the diversity of within-country inequality reduction episodes and synthesizes the experiences of several countries and policies in addressing the roots of inequality without compromising economic growth. Along the way, the report shatters some myths and sharpens our knowledge of what works in reducing inequalities. Finally, it also advocates for the need to expand and improve data collection—availability, comparability, and quality—and rigorous evidence on inequality impacts. This is essential for high-quality poverty and shared prosperity monitoring and the policy decisions such an exercise ought to support.

Extreme poverty is shrinking worldwide, but is still widespread in Africa

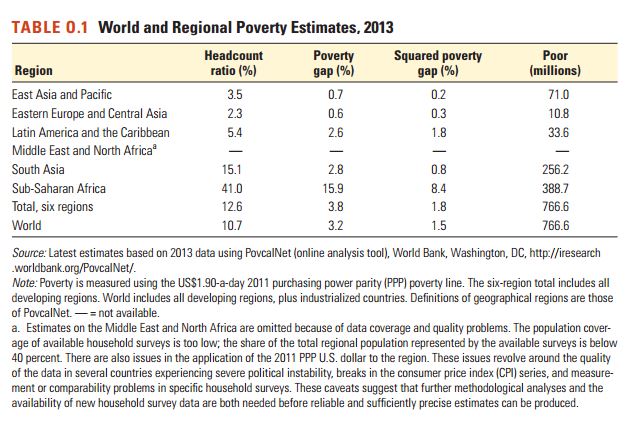

In 2013, the year of the latest comprehensive data on global poverty, 767 million people are estimated to have been living below the international poverty line of US$1.90 per person per day (table O.1). Almost 11 people in every 100 in the world, or 10.7 percent of the global population, were poor by this standard, about 1.7 percentage points down from the global poverty headcount ratio in 2012. Although this

represented a noticeable decline, the poverty rate remains unacceptably high given the low standard of living implied by the $1.90-a-day threshold. The substantial decline is mostly explained by the lower number of the extreme poor in two regions, East Asia and Pacific (71 million fewer poor) and South Asia (37 million fewer poor), that showed cuts in the extreme poverty headcount ratio of 3.6 and 2.4 percentage points, respectively. The former is explained in large part by lower estimates on China and Indonesia, whereas the decrease in South Asia is driven by India’s growth. The number of the poor in Sub-Saharan Africa fell by only 4 million between 2012 and 2013, a 1.6 percentage point drop that leaves the headcount ratio at a still high 41.0 percent. Eastern Europe and Central Asia’s headcount ratio shrank by about a quarter of a percentage point, down to 2.3 percent, while, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the ratio declined by 0.2 percentage points, to 5.4 percent (figure O.2). Both the extreme poverty headcount ratio and the total number of the extreme poor have steadily declined worldwide since 1990 (figure O.3). The world had almost 1.1 billion fewer poor in 2013 than in 1990, a period in which the world population grew by almost 1.9 billion people. Overall, the global extreme poverty headcount ratio dropped steadily over this period. Despite more rapid demographic growth in poorer areas, the forceful trend in poverty reduction culminated with 114 million people lifting themselves out of extreme poverty in 2013 alone (in net terms).

See Full Report Here