This is seriously aggravating the government’s capacity to absorb refugees in an already difficult environment of high unemployment and internally displaced people after decades of conflict.

While the Afghan government works to strengthen internal coordination and strategic planning, the international community also needs to play a vital role in providing financial and humanitarian support to avert a crisis and limit the damage to Afghanistan’s already challenging social and security conditions, and development prospects.

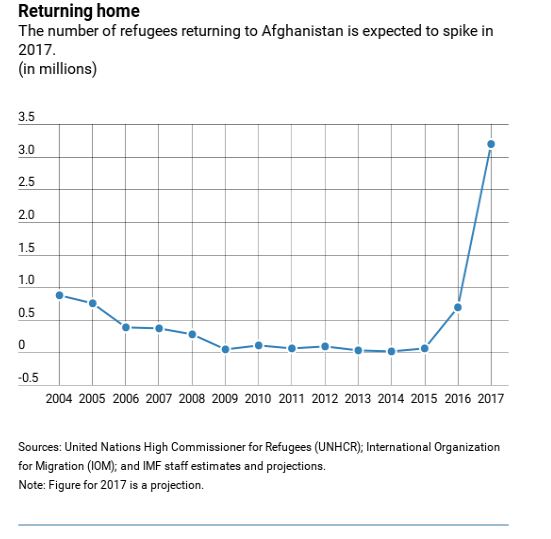

From trickle to flood

Aid officials estimate that more than 700,000 refugees returned to Afghanistan in 2016. Afghans—the second largest refugee group after Syrians, according to the UN’s refugee agency—are primarily returning from Pakistan, often not voluntarily. There are also returnees from Iran and to a lesser extent from Europe. Analysts project that up to 2½ million will follow over the next 18 months, which will add nearly 10 percent to Afghanistan’s population (see infographic below). To put this in perspective, this would be akin to 50 million migrants entering the European Union over a two-year period.

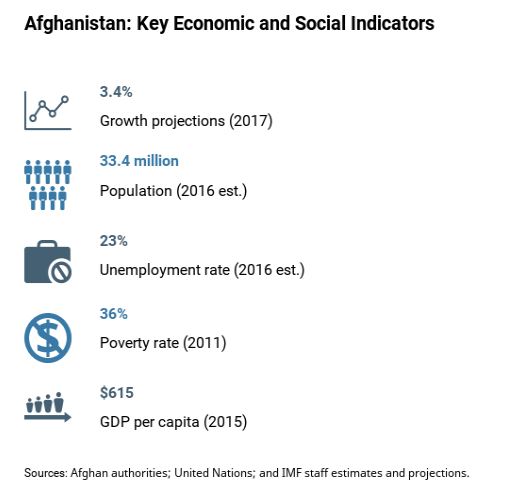

Many of the Afghans who lived abroad for decades are returning to a country facing conflict, insecurity, and widespread poverty. Given the difficult economic climate, prospects for returnees are generally poor. While there are also wealthier returnees, a typical returning refugee has a high risk of falling into poverty—they are typically laborers and workers in the informal economy with limited savings, or small business owners who are forced to liquidate their assets at fire sale prices.

Moreover, the prospects for absorbing returning refugees are further complicated by the existence of more than one million internally displaced people, the number of which significantly increased in 2016 as the insurgency intensified. Together with the large number of people who already live in poverty in Afghanistan, these problems will severely stretch the country’s capacity to cope.

Economics of reverse exodus

When a country receives a large influx of refugees over a short period, significant social and economic effects are likely, which are exacerbated in poorer countries like Afghanistan. On the positive side, returning refugees generally share the same culture as the local population, facilitating assimilation. In addition, increased spending, both by the private and public sectors, as well as increased output if the incoming refugees are able to find jobs, can contribute positively to economic growth both in the short and medium term.

However, increased demand for food, consumer goods, health services, and housing can put upward pressure on prices and rents, negatively affecting the poor. And the increased supply of labor is likely to raise the already very high unemployment rate and put downward pressure on wages. For instance, in the case of Lebanon—although there is little reliable data—surveys suggest that the inflow of refugees has had a significant impact on wages, particularly in the low-skill and youth sectors, where workers are most vulnerable. Equally important, the scale of the inflow has placed an undue burden on Lebanon’s already-stretched public services and infrastructure.

In Afghanistan, this raises the prospect of longer-term effects on economic and social development. For example, if basic services such as education and health cannot keep up with increased demand, some human capital—the stock of productive skills, talents, and health of the labor force—could be lost.

Robust strategy and coordination needed

The government has put in place policies for returnees and internally displaced people, that guides the implementation of the authorities’ response. Going forward, it will be critical that this strategy is implemented effectively to deal with increasing pressures on already stretched public services. These efforts should focus on the provision of basic services to meet the immediate survival needs of the returnees, cash transfers to sustain a basic living standard, assistance with job and housing search, all with a focus on urban areas, the location of choice for many refugees.

For example, Afghans with the appropriate documents were provided with a cash grant of $400 per person when they returned to Afghanistan. But, such grants have been suspended as Pakistan has extended the refugees’ stay until March 2017. Furthermore, the most vulnerable undocumented returnee families receive a one-month package of support at the border and a transportation cash grant. Internally displaced families also receive one-month support assistance.

Despite these efforts, undocumented refugees are particularly vulnerable with limited access to basic services. Given Afghanistan’s tight budgetary constraints, the international community—including bilateral and multilateral donors and aid agencies—can address these needs with financial support. To this end, the UN has appealed for $240 million in humanitarian assistance for the returning refugees (as part of the broader 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan for Afghanistan). The international community needs to rise to this challenge.

The IMF is also helping. The Fund has often provided economic policy advice and technical assistance to member countries dealing with large-scale refugee andmigration issues . With regard to Afghanistan, the IMF is supporting the government’s reform program through a concessional financing arrangement, the Extended Credit Facility, approved in July 2016. This arrangement provides Afghanistan with access to $45 million over three years, and offers highly concessional lending terms, that is, very low interest rates and long maturity.

The focus is on helping the government to maintain macroeconomic stability through these difficult times, and to lay the foundation for stronger and more inclusive private sector led growth, including by supporting the government’s efforts to strengthen government institutions, improve public service delivery, and support job creation.

This article originally appeared on www.imf.org , January 26, 2017. Original link.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in the article are not necessarily supported by CRSS.