a Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) report by Senior Research Fellow Muhammad Nafees

Pakistan’s blasphemy laws are controversial subject, with the public opinion in two distinct camps. One camp believes the laws to be absolutely essential, necessary for the protection of Muslims’ sentiments, especially as they apply to the finality of the Holy Prophet (PBUH). The other camp believes the laws to be draconic, leveraged by vested interested to primarily target minorities, and used to settle personal vendettas and disputes.

With a sudden upsurge in blasphemy allegations and cases, especially within the last two years, and major incidents of both lynching and sentencing to death of those accused of blasphemy, the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) has put together a comprehensive report that looks at the history of blasphemy allegations in the country, the number of people killed by vigilantes and charged mobs, the spread of this data across provincial, religious, gender, and socio-economic lines, and the principal complainants in blaspheming cases.

This report hopes to document the bulk of the data associate with blasphemy accusations and killings, and provide a concise snapshot of the depth and breadth of the problem, in the hopes that the government of Pakistan addresses this pressing issue, and works to alleviate the problem.

Background: 1947 – 2021

Overview

The debate around Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws and their socio-political consequences ranges from the argument “people disrespecting Islam should be punished” to “people are falsely accused to settle personal scores”. One segment of the society demands review of the blasphemy laws to prevent and discourage its abuse. Others deny any egregious misuse of the law for personal gains, albeit evidence suggests otherwise.

The latter arguments that most of the cases are either influenced by ideological inclinations or religious dogma. Often personal grudges morph into societal outrage with people taking the law in their own hands. They are not based on a careful factual review and analysis of the blasphemy-related incidents with due process of the law. The introduction of additional clauses in the blasphemy laws (PPC295-B, PPC295-C, 298A, B, C), and the addendums that introduced the death penalty and other punishments into the existing laws back in 1980 and 1986 have made the situation even worse.

Almost always, the murderers argue that the victims having committed an unpardonable religious crime, are ‘wajib-ul-qatal’, a highly controversial term that loosely translates to “worthy of being killed”.

This report takes a look at blasphemy-related violence, as reported in secondary sources such as newspapers, and tallies the victims, perpetrators, role of law enforcement, and number of charges. This is an effort to establish how prominent a problem the weaponization of blasphemy has become in Pakistan, and what the state needs to do to mitigate it on an emergency footing.

The state argues that those that commit murder in the name of blasphemy are summarily arrested, indicted, and prosecuted. The example often quoted is that of Mumtaz Qadri, who assassinated Salman Taseer, former governor of the Punjab province in January 2011. But the evidence on almost all other cases points to tardy and prolonged litigation. Further, Qadri has a shrine built around his grave, and given the concept of the afterlife in Islam, hardliner religious zealots would argue that he got the better deal. Most importantly, his execution seems to have done nothing to curb blasphemy-related violence across the country.

The Origins of the Blasphemy Laws

The British government had promulgated the blasphemy laws in 1860. Initially, four blasphemy laws IPC 295[1], 296[2], 297[3], and 298[4] were introduced. In 1927, the IPC 295 was supplemented by 295A[5] as a result of the famous case of Ilm-ud-din, a Muslim carpenter who killed Mahashe Rajpal for publishing the book ‘Rangila Rasul’.

The book was considered derogatory towards Muslims and the Holy Prophet (PBUH). Ilm-ud-Din was arrested, prosecuted and eventually executed, despite Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the counsel, requesting for commuting death sentence into life imprisonment. Nearly 600,000 people attended Ilm-ud-Din’s funeral.

It was the first major blasphemy related incident in the undivided sub-continent that witnessed stark violence resulting from an accusation. Coincidently, it was a period when the Indian society was going through a phase of political polarization especially along religious lines. This incident only exacerbated matters further. But crucially, it resulted in the introduction of 295A, which also became a trigger for the independence movement for India and Pakistan.

Blasphemy Accusations after Pakistan’s Birth

Nearly a year after the creation of Pakistan, communal hatred transformed into sectarian hatred between the Brelvi and Ahmadi sects of the Muslims (at this point, the Ahmadis had not yet been formally declared non-Muslims). On 11th August 1948, Major Mahmud, an Ahmadi by faith, was stoned and stabbed to death in Quetta. Justice Munir, in his report on Punjab Disturbances of 1953, quoted this incident in these words:

“The Muslim Railway Employees Association had organized a public meeting which was held on the evening of 11th August 1948. Some maulvis (clerics) addressed the gathering and, the subject selected by each one of them for his speech was khatm-i-nubuwwat (the finality of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)). In the course of these speeches, references were made to the Qadianis’ (Ahmadis’) kufr (disbelief – a loaded word with negative connotation) and the consequences thereof. While the meeting was still in progress, Major Mahmud, on his return from a visit to a patient, passed by the place where the meeting was being held. His car accidentally stopped near the place of the meeting.

Efforts to re-start the car failed. Just then a mob came towards the car and pulled Major Mahmud out of it. He attempted to flee but was chased and literally stoned and stabbed to death, his entire gut having come out.”

Two more Ahmadis were killed in 1950[6]. In 1953, the province of Punjab became the center of disturbances led by religious parties who were demanding that the Ahmadis be declared a non-Muslim minority and removed from their offices as well. The military was called in to suppress these disturbances and it took more than three months before the situation was brought to normal.

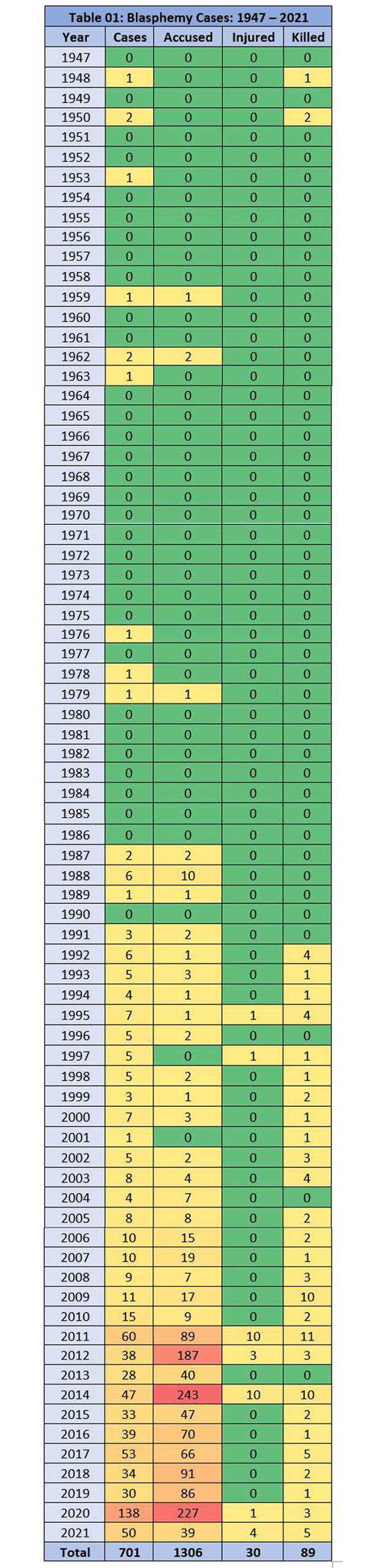

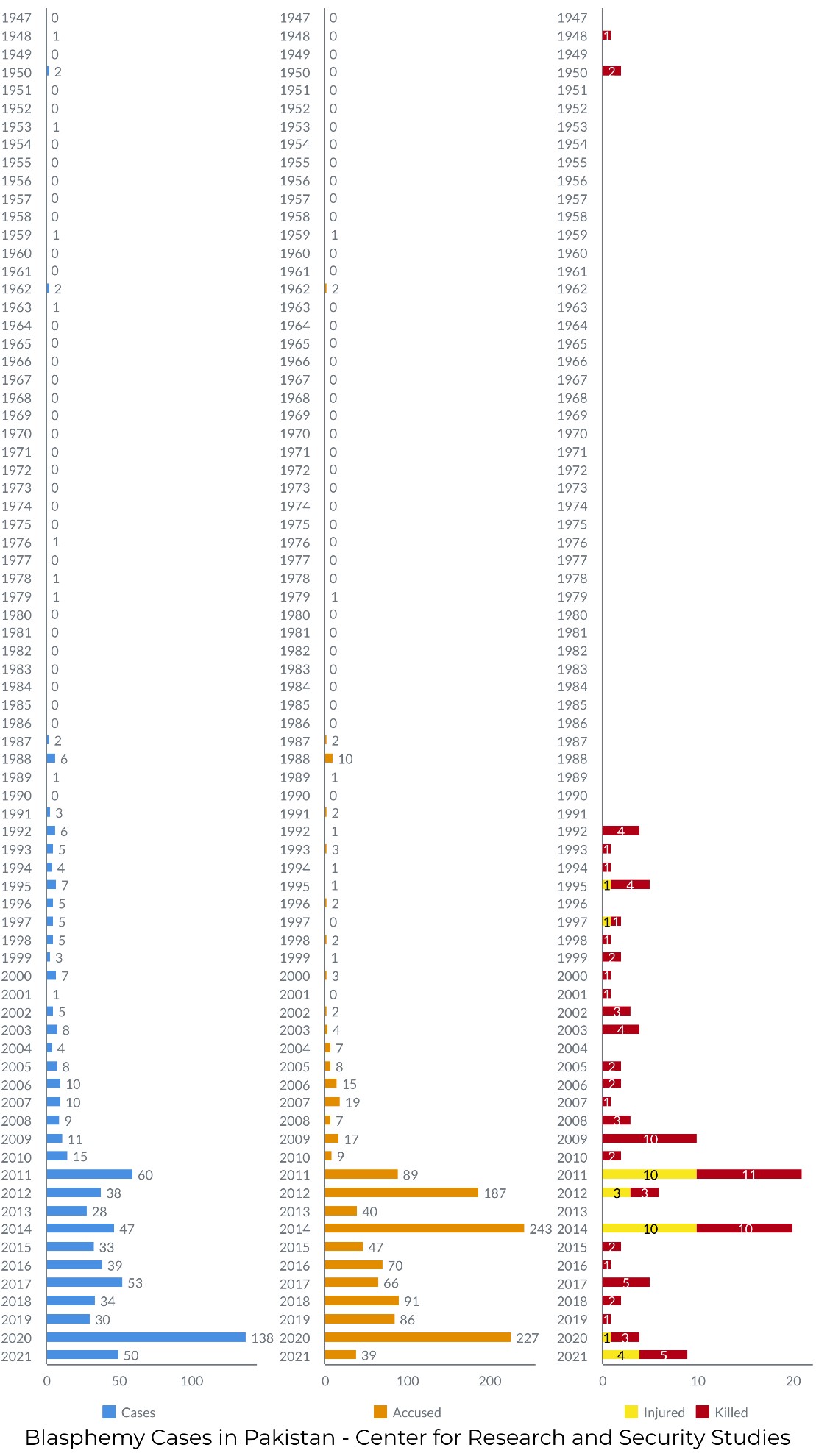

No extrajudicial killing of any alleged blasphemer or follower of Ahmadi faith was reported from 1954 to 1992. Though cases of blasphemy were reported during this period, such cases surged after 1988, when supplemental clauses were added to the blasphemy law PPC 295-B[7], C[8], 298-A[9], B[10], & C[11] (see table 01).

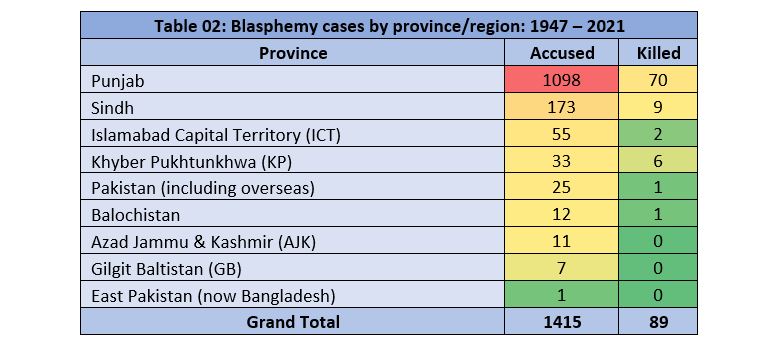

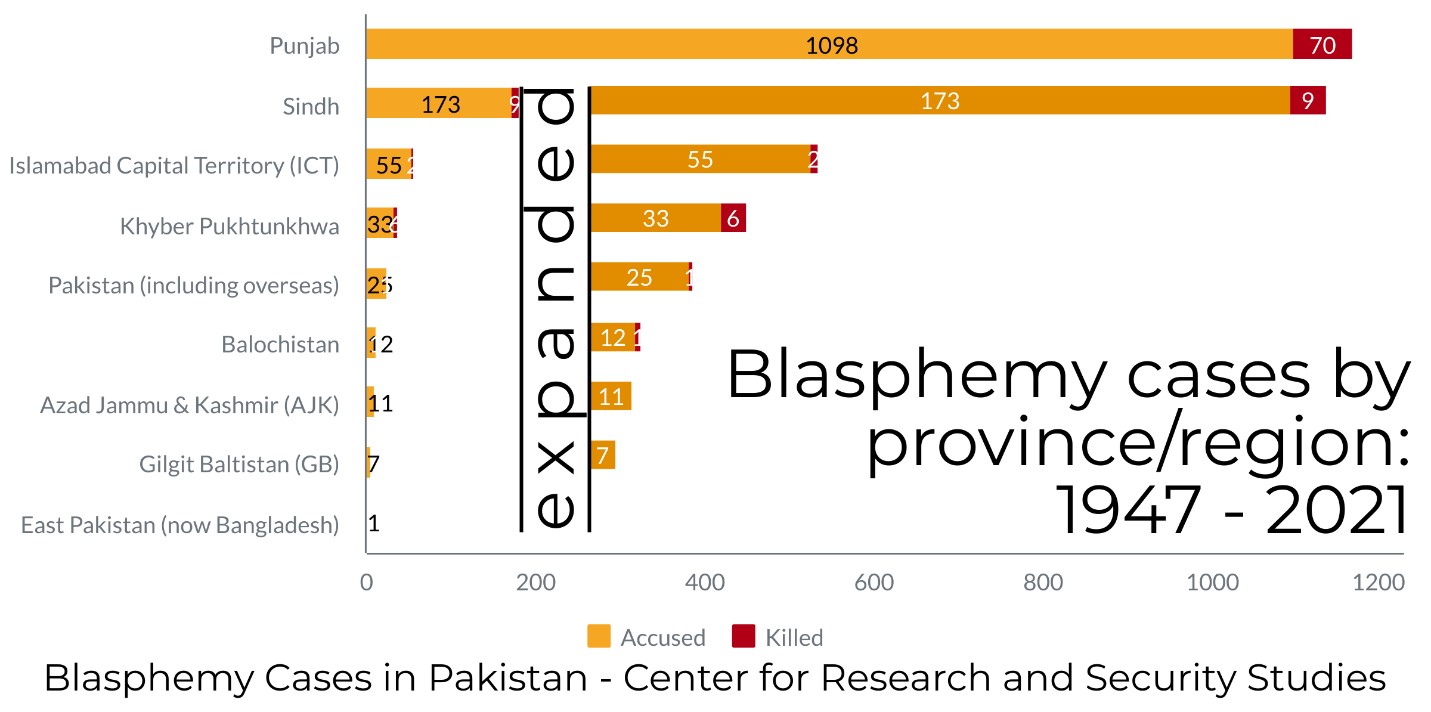

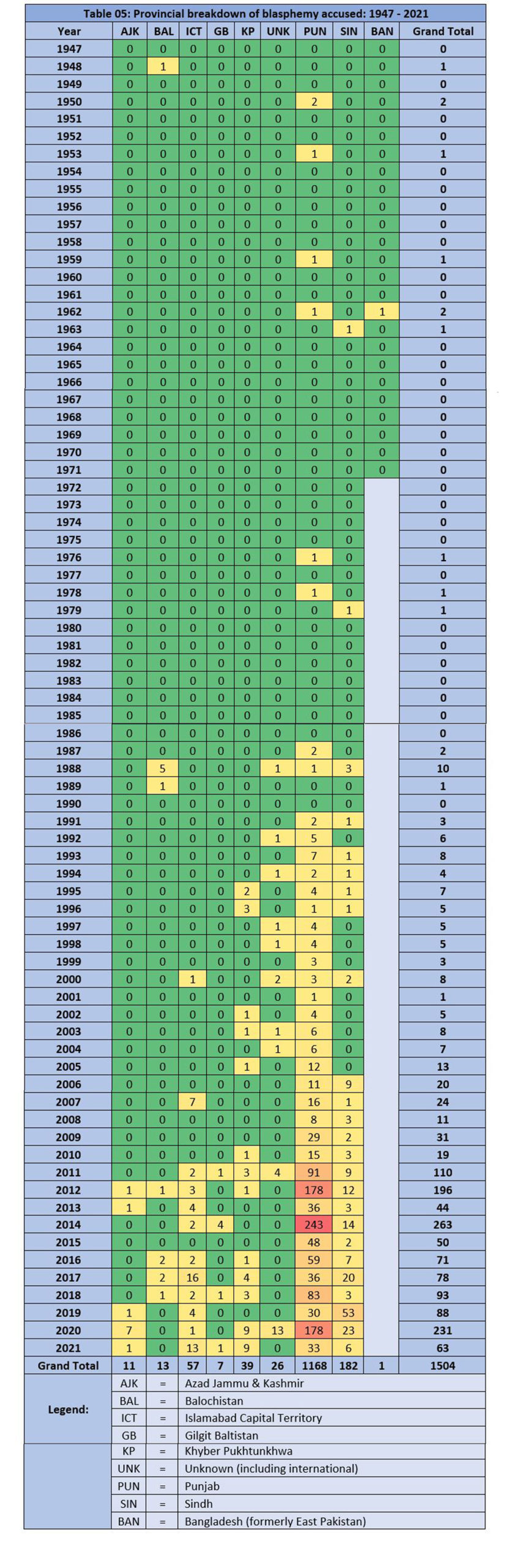

As of 2021, 89 people have been extrajudicially killed, from roughly 1,500 accusations and cases. The actual number is believed to be higher because not all blasphemy cases get reported in the press. More than 70% of the accused were reported from one province – Punjab (1,098), followed by Sindh (177), Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT) (55), Khyber Pukhtunkhwa (KP) (33), Balochistan (12), and Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK) (11). Note that the capital of the country had more cases of blasphemy than KP and AJK jointly had. Cases where the location was unclear have been marked in the data from Pakistan overall.

One blasphemy case was reported from what is now Bangladesh when it was part of the country. Four cases were reported from Thailand where Pakistani people were involved. In one case, a Pakistani man had extrajudicially killed his Thai girlfriend and cut her body into several pieces after blaming her of committing blasphemy. In another case, three Ahmadis, who had migrated to Thailand due to facing blasphemy charges, were being chased by their accusers with an intent to bring them back in the country and prosecute them for the crime they had allegedly committed[12].

Alarming is the increasing trend of both cases, the accused, and extra-judicial killings, particularly in the last few years. From 1948 to 1978, only 11 cases of blasphemy were recorded, of them three were extra-judicially killed. From 1987 to 2021, these cases went up by about 1,300%.

Though the rise of any crime always generates an alert among security officials and responsible institutions, this crime appears to have no established pattern and most of the police websites remain silent on the occurrence of this crime.

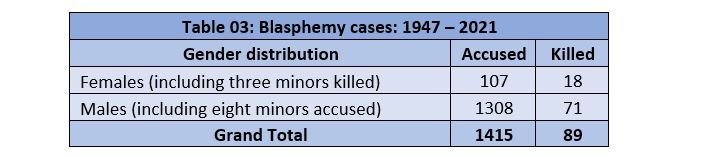

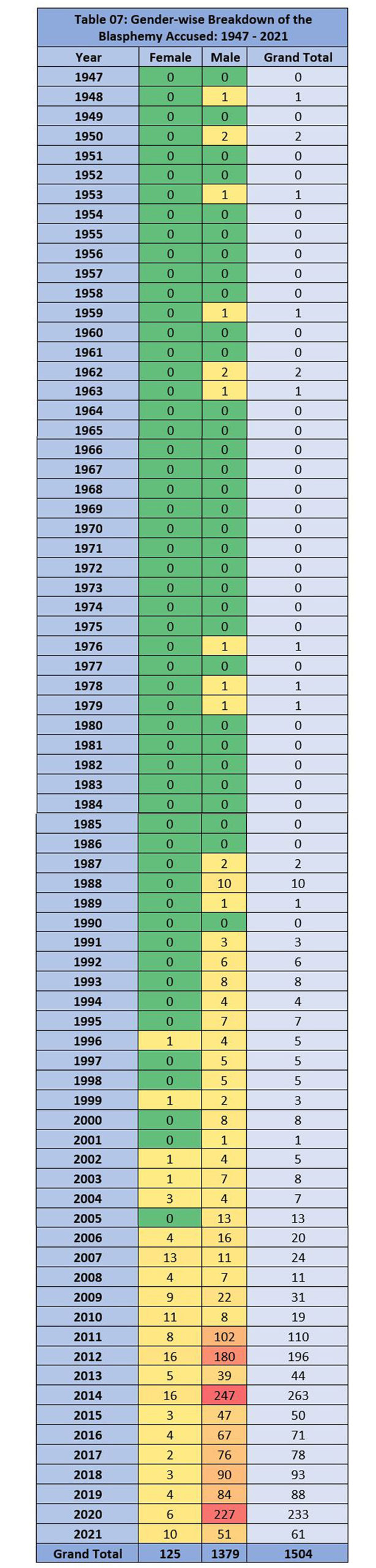

Before the introduction of additional clauses of blasphemy laws during the 1980-86 period, no female was ever accused of having committed blasphemy. Even after the introduction of additional laws, it took nearly a decade until a woman, Bushra Taseer from Sindh, was charged under Section 295-C in 1996. A tailor had alleged that she had given him cloth to stitch, which had a religious inscription on it[13].

From 1947 to 2021, 107 women had been accused of blasphemy and 18 of them were extrajudicially murdered, two of them minors. On 28 July 2014 an elderly woman and two minor girls lost their lives to a charged mob, which attacked the houses of Ahmadis in Gujranwala over an alleged act of blasphemous posting on Facebook. Regrettably, all victims of this mob attack were innocent and had not committed any act of blasphemy because the accused boy was not at home when the mob attacked[14].

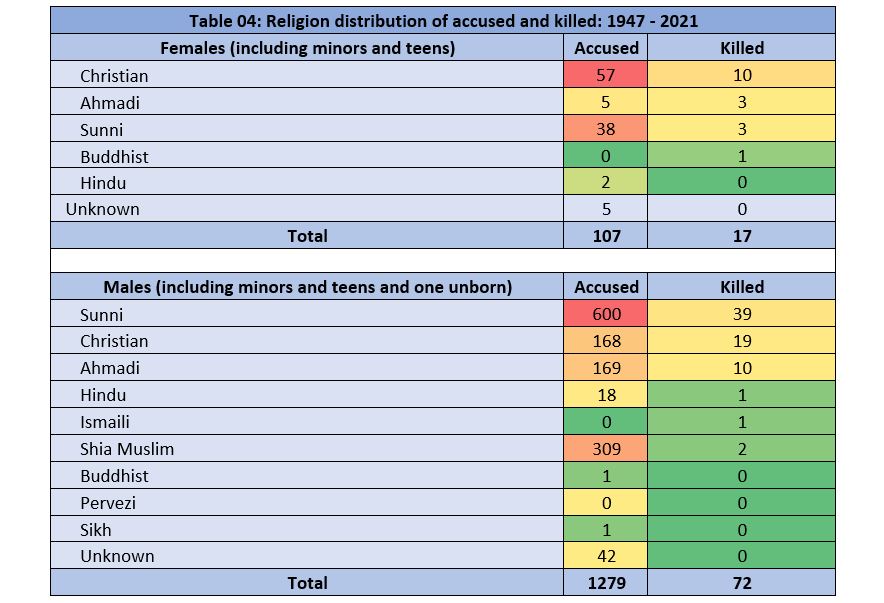

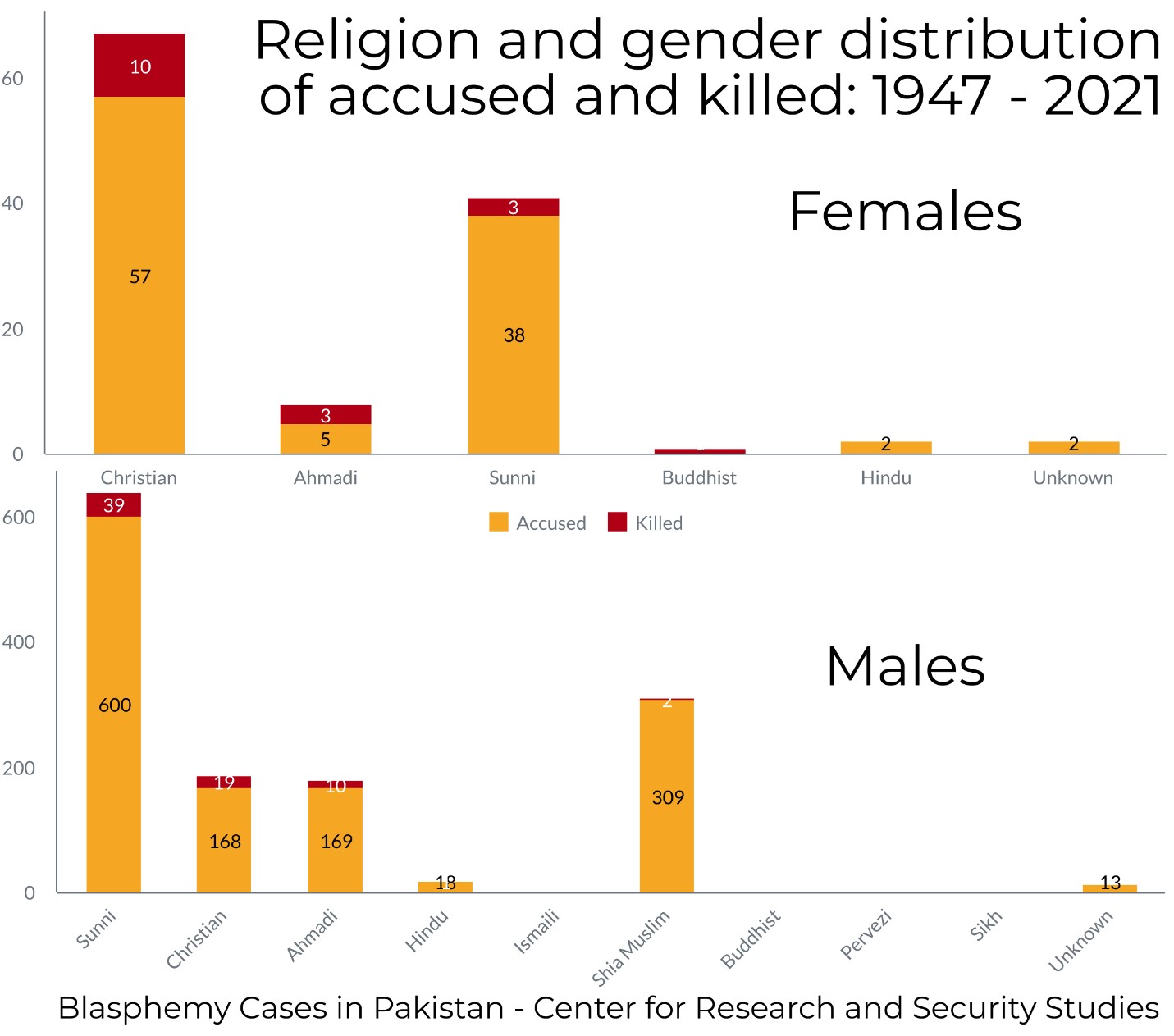

Among the female alleged blasphemers, the highest number was of Christian women (65), followed by the Muslim (37), Ahmadi (8), Hindu (2), Buddhist (1) and two women of unknown religious background. Males, on the other hand, were largely Muslims, who were accused of this offense (930) including all Muslim sects that make 70% of all male blasphemers). The remaining male accused are Christians (186), Ahmadis (179), Hindus (16), and Sikhs (1). The percentage of the non-Muslims’ population in the country is under 5%.

Provincial Level Incidents of Blasphemy Accusations: 1947 – 2021

The district-wise data above may be useful for identifying recent hotspots, but how are the main provinces/regions faring in terms of blasphemy accusations? Data shows that Punjab accounts for the overwhelming majority of accusations (79%), followed by Sindh (12.3%), and a distant third, the Islamabad Capital Territory (2.78%), despite accounting for less than one percent of the population.

Religious Communities Accused of Blasphemy: 1947 – 2021

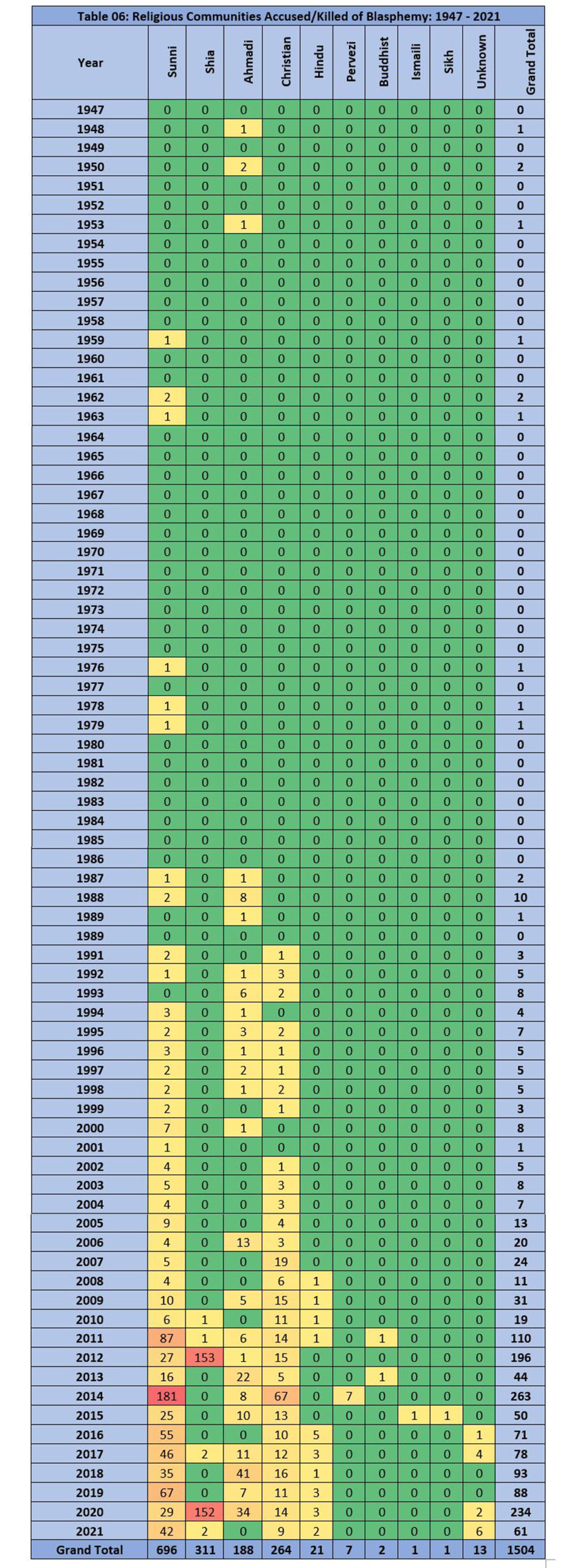

In the earlier section, we briefly discussed the number of persons from all those religious communities who were accused of blasphemy. This section divides that data by the reported faith of the accused. After the introduction of additional blasphemy laws (see the backgrounder section above) during the Zia period (1980-86), ten persons from the Ahmadi community were accused of blasphemy in three years (1987-9) along with three individuals from the mainstream sect.

From 1991-2000, 16 Ahmadis, 13 Christians, 24 Sunnis and one convert were accused of blasphemy. Christians had found themselves accused of a crime for the first time since the promulgation of blasphemy laws in 1860. After 1994, not a single year went by without having no report of a Sunni blasphemer, followed by the Christians. Ahmadis and Hindus also followed this trend after 2008 with some interruptions (table 07).

Gender-wise Breakdown of the Blasphemy Accused: 1947 – 2021

The vast majority of those accused of blasphemy are males.

The first recorded incident of a female being accused of blasphemy occurred in 1996 after a tailor had alleged that a woman had given him cloth to stitch with religious inscription on it. An unidentified Muslim woman who was said to be mentally sick was burnt alive by a mob in Rahim Yar Khan in 1999. From 2002 onward, with the exception of 2005, at least one female was accused every year (table 08).

Extrajudicial Killing on Blasphemy Charges: 1947 – 2021

The most prominent case of extrajudicial killing on blasphemy grounds was of Salman Taseer, the sitting Governor of Punjab by his own police guard. He is one of 84 people killed over blasphemy accusations.

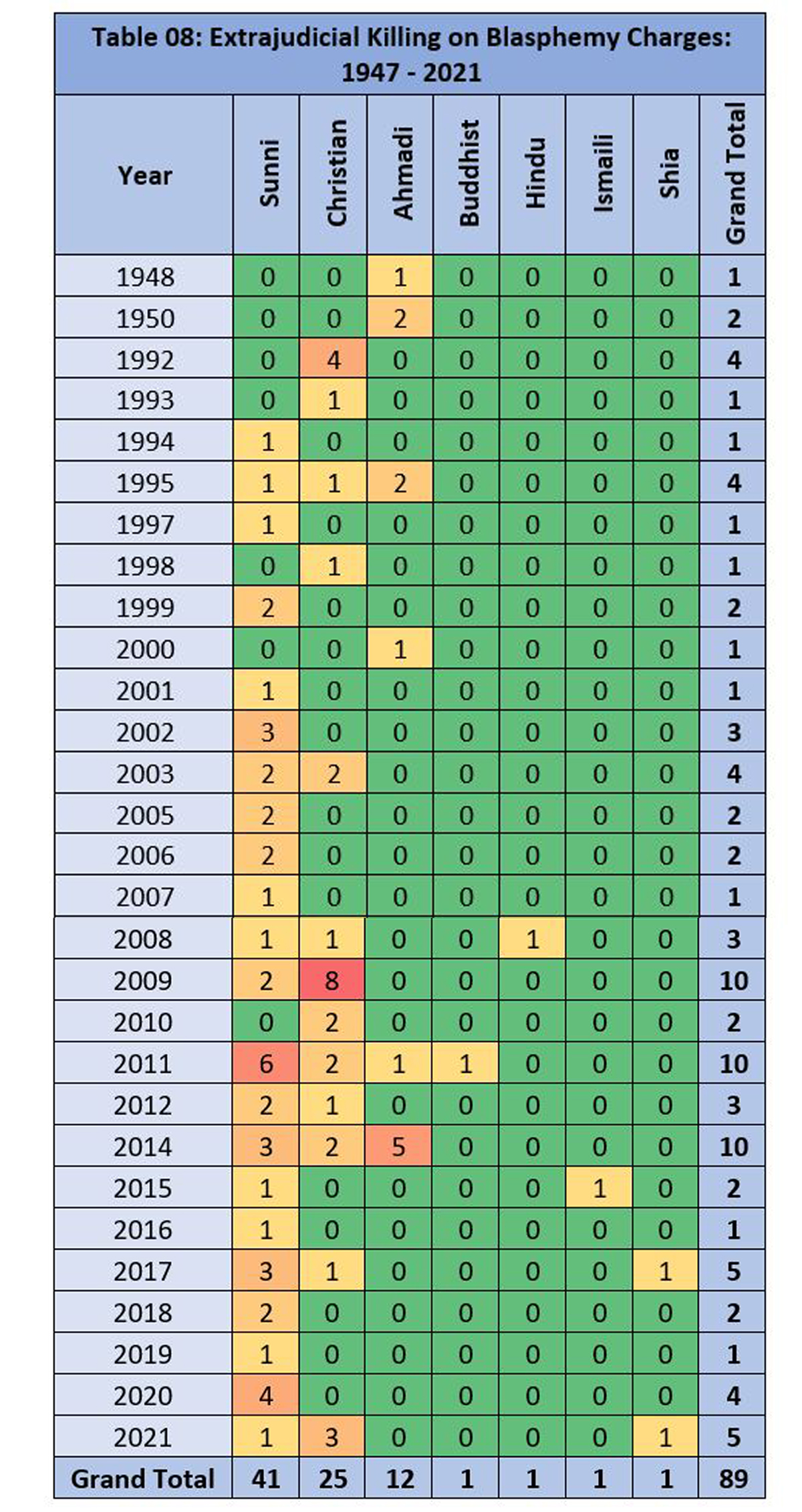

From 1948 to 1993, eight persons were extrajudicially killed in the country and all of them were non-Muslims. Four of them were Ahmadis and the other four were Christians. In 1994, for the first time after the introduction of blasphemy laws in 1860, an ostensibly devoted Muslim and Hafiz-e-Quran, Farooq Sajjad, became a victim of a brutal murder. He was first stoned to death and later the burnt corpse was dragged in the street[15]. Ironically, he was affiliated with Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), a religious party that was instrumental in adding death penalty to the blasphemy law PPC 295-C[16]. Hafiz Farooq Sajjad’s wife in Gujranwala fought the case against the culprits for some time and then surrendered to the circumstances that forced her to discontinue this case once she lost her father and the financial support from JI[17].

Of the remaining 84 killed, 45 were Sunni Muslims who lost their lives from the 1994 to 2021 period. The remaining 39 were other religions or sects, including 25 Christians, 12 Ahmadis, a Budhist, and a Hindu. Roughly 77.4% of those killed were from Punjab (65).

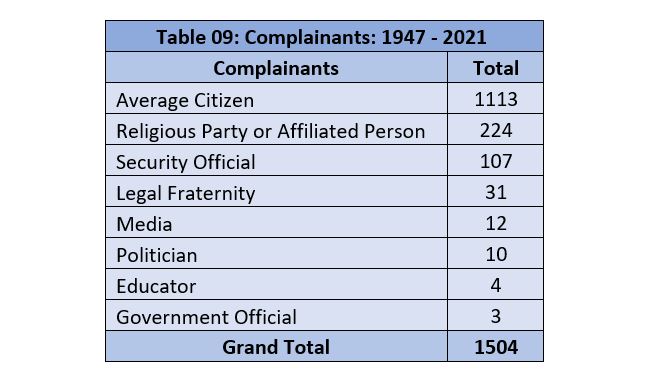

Majority of the complainants of blasphemy cases were average citizens. However, people from various professions and backgrounds also contributed blasphemy allegations. The most prominent group is comprised of religious groups and affiliated persons (204), followed by security officials (102). Among the 1,082 the accusers came from all backgrounds, socio-economic classes, ages, affiliations, and professions (table 10).

Categorization of Individuals Accused of Blasphemy: 1947 – 2021

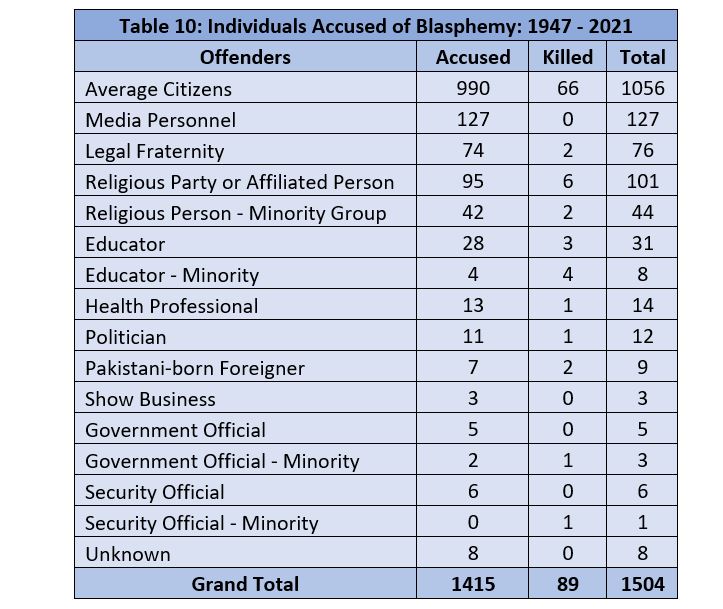

The majority of the accused are from the common people (1016) followed by media persons (100), members of the legal fraternity (76), religious party members and affiliated persons (97), religious persons from minority groups (44), educators (26), health professionals (14), politicians (11), educators from minority groups (8), social media (8), Pakistan-born foreigners (6), government officials (5), showbiz persons (5), security personnel (4), and many others.

A total of 84 people were extrajudicially murdered on blasphemy charges and the majority of them are also from the common people (63), followed by religious persons (5), educators from minority community (4), educators (3), members of the legal fraternity (2), and one each from health professional, politician, government official from minority community and a security person (table 11).

Blasphemous Accusations against Dominant Sunni Muslim Faith: 2011 – 2020

There were some cases of blasphemy reported in the press where the perpetrators were either unknown or beyond the reach of the law enforcement agencies. Of the ten cases of such offenses, eight were committed against the Muslim faith, one against an Imambargah, and one against the Holy Quran. Islamabad, the capital of the country, reported most of these cases (5) while Sindh and KP recorded 2 each case and one case was from Punjab.

Those who allegedly committed blasphemy were online users with allegedly blasphemous content on social media and some websites like Bhainsa, Mochi, and Roshni, as well as on YouTube. Unfortunately, the Shia community, a minority sect of the Muslim faith, also experienced offenses against their religious places in the country. One such incident was reported on 18 March 2012, when the Jail Superintendent Tariq Babar and Deputy Superintendent Mehr Ashraf were accused for the demolition of Imambargahs and accused them of defiling holy books[18].

Blasphemous Accusations against Non-Muslim Faiths: 2011 – 2020

The blasphemy law PPC 298-C says that any Ahmadi posing as a Muslim or calling his faith Islam will be considered blasphemous and punishable under the law. Enraged mobs often extrapolate this wording to also include the mere existence of Ahmadi places of worship. In their belief they take this step to rectify a ‘blasphemous act of Ahmadi community’. The Hindu community is targeted because of historical baggage and Pakistan inability to differentiate between India’s Hindu majority, and Pakistani Hindus. The Christians, much like the Ahmadis and Hindus, are easy targets because the state response is so weak. In fact these three communities have also been targeted by fledging terror outfits, as they are easy targets.

Ten persons involved in removing the foundation stone of a Church and holy verses of Bible in Okara were booked under section PPC 295A but no further information is available about the apprehension and prosecution of the culprits for this crime. Talking on such a lack of action against the culprits, the president of the Masiha Milat Party, Aslam Pervaiz Sohotra, made this comment: “There are some [some politicians – Ed.] who say that Christians are protected and safe and that they enjoy equal rights. I ask them: how many guilty have been punished for these incidents? On the contrary, instead of punishing them, these culprits are considered heroes. And this mentality terrifies and hurts minorities in Pakistan. All this brings shame to Pakistan in the international community[19].”

Similarly, on August 5, 2021, dozens of people vandalized a Shree Ganesh Hindu temple in Bhong, upset over the bail of an 8-year old boy, accused by a local cleric of blasphemy, as the boy urinated while being scolded by the cleric for accidentally wandering into the local seminary[20].

This later incident marked the 8th such incident in the prior 18 months, as attacks against non-Muslims intensify, with the perpetrators fully aware of the weak response by the state for such acts. These incidents are being mentioned as they are not included in this sub-section of the report, which recounts the incidents for the 10-year period between 2011 and 2020.

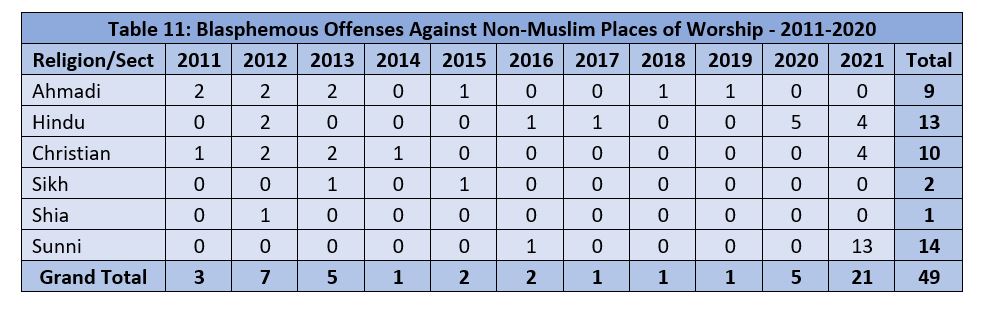

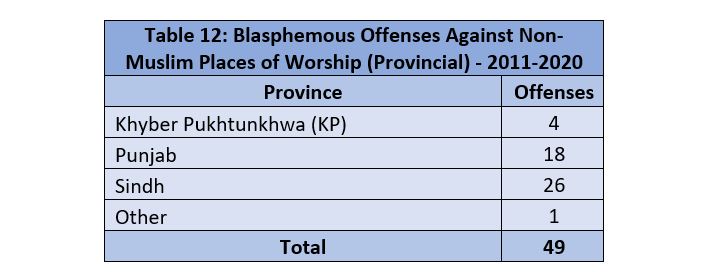

The desecration of the non-Muslims’ religious places is an act of blasphemy that falls within the blasphemy law PPC 295A. A number of religious places were desecrated in Pakistan by violent mobs for various reasons, as documented below for the last ten years alone (table 12).

These offenses were mostly committed against the religious places and Holy Scriptures of different religious communities. The table 13 shows that the highest number of such crimes were committed, predictably, in Punjab (14), followed by Sindh (8), and then KP (4). Coincidentally, both provinces have larger concentration of the three primary minority communities in the country – Christians and Ahmadis in Punjab, and Hindus in Sindh. On the other hand, KP has a very marginal population of the non-Muslims living in the province. Yet, the offenses against the non-Muslim are about 15% of the total offenses committed in the country.

The offenses against the religious places and holy scripts of the non-Muslims were reported by Ahmadi, Christian, Hindu, and Sikh communities. While the dominant Sunni Muslim population has always reacted furiously against alleged blasphemy accusations, their reaction to the desecration of the non-Muslim’s religious places was always inversely opposite and reflective of a kind of indifference or complicity.

Some prominent examples are documented below.

A high-profile example was that of an angry mob of Tehreek-e-Labaik Ya Rasool led by Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaaf (PTI) leader Hamid Raza had attacked a historic Ahmadi worship place on May 25, 2018 in Sialkot. Video clips of this incident went viral showing the PTI leader thanking local police administration for their assistance[21].

On October 3, 2014, the foundation stone of a church and holy verses of Bible were removed by a mob here in Village 3/4L of Okara District. According to the police an FIR was registered under section 295-A and 506-B (criminal intimidation) against ten people for damaging the church and defaming the cross[22].

On October 27, 2019 an operation headed by the assistant commissioner of Hasilpur, Mohammad Tayyab, led to the destruction of the mihrab of the Ahmadi worship place. Tayyab was accompanied by police officers and officials of the local development authority[23].

In May 2012, some clerics in Sultanpura, Lahore had complained that an Ahmadi place of worship looked too much like a mosque and they deemed it necessary to have the building’s dome demolished. Two people had filed an application with the police, requesting that they register an FIR against the Ahmadis under the blasphemy laws – 298-C and 295-B of the Pakistan Penal Code – “for depicting themselves as Muslims”. Policemen scratched out Quranic verses written on the walls of an Ahmadi place of worship and ordered them to cover up short minarets at the entrance as they made the place look like a mosque[24].

Other than Ahmadi’s worship places, the worship places of Christians, Hindus, and Sikhs were also subjected to desecration and in most of the cases the enraged mobs were involved. The last incident of such blasphemous act was occurred on December 30, 2020 when around 1,500 people led by a cleric descended on a historic Hindu temple in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa’s Karak district and they vandalized some portion of the temple and set it on fire[25]. Initially, some arrests were made but hardly after some time, a jirga was held wherein the Karak residents apologized for the incident and the Hindu community, in return, pardoned the culprits[26].

“The community would provide aid and employ efforts to secure release of the accused from the prison in the light of the recommendations of a jirga,” said Pakistan Hindu Council Chairman and PTI lawmaker Dr. Ramesh Kumar while announcing the decision in a press conference in Peshawar.

This wasn’t the only case where the non-Muslim community showed its tolerance to the Muslim offenders of their faith, a similar case against Christian faith was reported on 21 September 2012 when angry mobs set the Sarhadi Lutheran Church in Mardan on fire along with countless holy books. The local Christian community later pardoned the perpetrators[27].

While the minority communities show their tolerance in dealing with the cases wherein their religion was defiled by the majority community, a similar offense by minority community finds no tolerance from the majority community. Adnan Prince, a Christian, was reported on 13 January 2016 to have been languishing in prison for two years under blasphemy charges (295-A, 295-B, and 295-C). His crime was that he had allegedly passed uncharitable remarks regarding a leader of the Jamatud Dawa (JuD)[28].

Salamat Masih, 11, Manzoor Masih, 38, and Rehmat Masih, 44, were accused of writing blasphemous remarks on a wall belonging to a mosque. Although the mother of Salamat Masih said that her son did not know how to read[29].

Samuel Masih, a Christian, accused of defiling a mosque by spitting on its wall, was killed while he was in police custody. A police officer, who used a hammer to kill him, claimed that it was his duty as a Muslim to kill Masih.

As may be illustrated through these examples, these three communities in particular may be targeted by enraged mobs, egged on by all manner of individuals ranging from cleric, local leaders, and even lawmakers and policemen.

These are a few examples of how blasphemy offenses committed against the non-Muslim faiths are treated in the country in comparison with the similar offenses against the Muslim faith. If we claim that we treat all faiths equally and show similar respects to other faiths as we show to our own, it has to be exhibited in our acts.

The misuse of blasphemy laws is often described by the court as an unlawful act. The Islamabad High Court has previously suggested the legislature to amend the existing laws to give equal punishment to those who level false blasphemy accusations[30]. The jurisdiction system is also found by the higher courts as careless or complicit in handling cases of blasphemy.

On April 4, 2014, an additional district and sessions judge in Toba Tek Singh had awarded death sentence and a fine of Rs100,000 each to Shagufta Kausar and Shafqat Masih under Section 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC), read with Section 34, for sending blasphemous messages on the phone. An LHC division bench, comprising Justice Shahbaz Ali Rizvi and Justice Tariq Saleem Sheikh, heard the appeal for three straight days and on June 3 allowed the appeal, saying that the prosecution had failed to establish the case against the couple beyond doubt. “We are dismayed that the learned Additional Sessions Judge has decided the case in a slipshod manner. We allow this appeal and set aside the impugned judgment dated 4.4.2014. The appellants are acquitted of the charge,” read the judgment[31].

The Pakistani society is highly polarized on this issue and its reflection can be found among lawyers and judges as well who refrain from taking up blasphemy cases fearing violent retaliations once they announced the verdict. There are lawyers and former judges who hail extrajudicial murderers as saints – the case of Mumtaz Qadri, the security guard of the former Governor of Punjab, is a good example of such a division within the legal fraternity.

Even after acquittal from blasphemy cases, the accused remain vulnerable to extrajudicial killing. On 4 July 2021, a policeman killed a man with a cleaver over blasphemy allegations years after the victim was acquitted of the charge by a court. On December 4, 2021, a Sri Lankan national was lynched by a charged mob over accusations of blasphemy. The list goes on.

The blasphemy related incidents covered in this report simply reflect another stark reality: the laws and reactions are not made equal for all. While high-profile individuals such as the prime minister and a chief of the army staff have been accused, the reaction and retribution was not nearly as pronounced. It must be said that even someone as powerful as the prime minister had to submit his apology to save himself from the outrage of the religious clergy. The people belonging to the lowest segment of the society were not as lucky. The same courtesy is not extended to the average Pakistani.

The blasphemy debate in the country needs to be addressed once and for all, taking into account the recommendations of the judiciary for false accusations. That one factor alone may lead to a dramatic decline in the number of cases, as there are next to no repercussions currently for the complainants lying under oath.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] “Whoever destroys, damages or defiles any place of worship, or any object held sacred by any class of persons with the intention of thereby insulting the religion of any class of persons or with the knowledge that any class of persons is likely to consider such destruction, damage or defilement as an insult to their religion, shall be punished with imprisonment … for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both.”

[2] Causing a disturbance to an assembly engaged in religious worship…

[3] Trespassing in place of worship or sepulcher, disturbing funeral with intention to wound the feelings or to insult the religion of any person, or offering indignity to a human corpse…

[4] “Whoever, with the deliberate intention of wounding the religious feelings of any person, utters any word or makes any sound in the hearing of that person, or makes any gesture in the sight of that person or places any object in the sight of that person, shall be punished with imprisonment … for a term which may extend to one year or with fine, or with both.”

[5] “Whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class of citizens … , by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations insults the religion or the religious beliefs of that class, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both.”

[6] “In 1901 Mirza Sahib claimed to be a ‘zilli nabi’ and by an advertisement ‘Ek ghalati ka izala’, explained the doctrine of khatm-i-nubuwwat to mean that after the death of the Holy Prophet of Islam no nabi would appear with a new shari’at but that the appearance of a new prophet without a shara’a was not contrary to the doctrine of khatm-inubuwwat. In a public lecture in Sialkot in November 1904, Mirza Sahib also claimed to be a Maseel-i-Krishan.” Excerpt from Justice Munir’s report on Punjab disturbances of 1953, Pp 10.

[7] Defiling, etc., of Holy Qur’an: Whoever wilfully defiles, damages or desecrates a copy of the Holy Qur’an or of an extract therefrom or uses it in any derogatory manner or for any unlawful purpose shall be punishable with imprisonment for life.

[8] Use of derogatory remarks, etc., in respect of the Holy Prophet: Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation or by any imputation, innuendo, or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) shall be punished with death, or imprisonment for life, and shall also be liable to fine.

[9] Use of derogatory remarks, etc., in respect of holy personages: Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation, or by any imputation, innuendo or insinuation, directly or indirectly, defiles the sacred name of any wife (Ummul Mumineen), or members of the family (Ahle-bait), of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him), or any of the righteous Caliphs (Khulafa-e-Rashideen) or companions (Sahaaba) of the Holy Prophet (peace be upon him) shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.

[10] Misuse of epithets, descriptions and titles, etc., reserved for certain holy personages or places:

- Any person of the Quadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves ‘Ahmadis’ or by any other name who by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation-

- refers to or addresses, any person, other than a Caliph or companion of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), as “Ameer-ul-Mumineen”, “Khalifatul- Mumineen”, Khalifa-tul-Muslimeen”, “Sahaabi” or “Razi Allah Anho”;

- refers to, or addresses, any person, other than a wife of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), as “Ummul-Mumineen”;

- refers to, or addresses, any person, other than a member of the family “Ahle-bait” of the Holy Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), as “Ahle-bait”; or

- refers to, or names, or calls, his place of worship a “Masjid”;

shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, and shall also be liable to fine.

- Any person of the Qaudiani group or Lahori group (who call themselves “Ahmadis” or by any other name) who by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representation refers to the mode or form of call to prayers followed by his faith as “Azan”, or recites Azan as used by the Muslims, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, and shall also be liable to fine.

[11] Person of Quadiani group, etc., calling himself a Muslim or preaching or propagating his faith: Any person of the Quadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves ‘Ahmadis’ or by any other name), who directly or indirectly, poses himself as a Muslim, or calls, or refers to, his faith as Islam, or preaches or propagates his faith, or invites others to accept his faith, by words, either spoken or written, or by visible representations, or in any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years and shall also be liable to fine.

[12] Irfan, 27, left his village Taban in Punjab’s Sheikhupura district after he and his two brothers Furqanul Mulk, 21, and Umer Sultan, 31, were held under Pakistan Penal Code’s Section 298-C, which prohibits Ahmadis from calling themselves Muslim or “in any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims”. A police case was lodged against them but residents refused to calm down, and the three men decided to leave the country. “When people of the village learnt about our detention and asylum applications, they approached the Sheikhupura District police chief and submitted an application seeking our repatriation to Pakistan calling us traitors who had maligned the country abroad,” Irfan told The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 17, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/202641/pakistans-persecuted-minorities-for-ahmadi-refugees-in-thailand-problems-double-back-home.

[13] Imtiaz, S. (2010, December 13). In the name of religion: 32 blasphemy cases in Sindh. The Express Tribune. Retrieved, April 17, 2021, from http://tribune.com.pk/story/89374/in-the-name-of-religion-32-blasphemy-cases-in-sindh/.

[14] Tanveer, R. (2014, July 28). Gujranwala blasphemy case: Ahmadis point fingers at ‘silent spectators’. The Express Tribune. Retrieved, April 17, 2021, from http://tribune.com.pk/story/742273/gujranwala-blasphemy-case-ahmadis-point-fingers-at-silent-spectators/.

[15] Dawn. (2012, September 19). Timeline: Accused under the Blasphemy Law. Dawn. Retrieved, April 17, 2021, from https://www.dawn.com/news/750512/timeline-accused-under-the-blasphemy-law.

[16] Sethi, N. (2018, May 11). Past, Present, Future. The Friday Times. Retrieved, April 17, 2021, from https://www.thefridaytimes.com/past-present-future/.

[17] Kohari, Alizeh. (2017, January 11). For the Love of God: Forgiveness in the Aftermath of Blasphemy in Pakistan. The Wire. Retrieved, April 17, 2021, from https://thewire.in/south-asia/98266.

[18] Correspondent. (2012, March 18). Imambargahs’ demolition: Shia Ulema Council rejects ‘joint’ inquiry. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 20, 2021, from http://tribune.com.pk/story/351498/imambargahs-demolition-shia-ulema-council-rejects-joint-inquiry/.

[19] Khokhar, S. (2021, May 18). Muslim mob attacks a Christian village. Houses looted, men and women beaten and injured (VIDEO). AsiaNews.it. Retrieved May 20, 2021, from http://www.asianews.it/news-en/Muslim-mob-attacks-a-Christian-village.-Houses-looted,-men-and-women-beaten-and-injured-(VIDEO)-53169.html.

[20] Mehmood, A. (2021, August 5). Mob vandalises Hindu temple after boy granted bail. The Express Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2314027/mob-vandalizes-hindu-temple-after-boy-granted-bail.

[21] Imran, W. (2018, May 24). Mob attacks historic Ahmadi worship place in Sialkot. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/1717928/1-mob-razes-historic-ahmadi-property-sialkot/.

[22] Tanveer, R. (2014, March 4). Okara residents allegedly vandalize under-construction church. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from http://tribune.com.pk/story/678809/okara-residents-allegedly-vandalise-under-construction-church/.

[23] Naya Daur. (2019, October 27). Ahmadi Worship Place Destroyed By Authorities in Bahawalpur. Naya Daur. Retrieved April 21, 2021 from https://nayadaur.tv/2019/10/ahmadi-worship-place-destroyed-by-authorities-in-bahawalpur/.

[24] Tanveer, R. (2012, May 3). Anti-Ahmedi laws: Police act as worship place ‘looks like a mosque’. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/373787/anti-ahmedi-laws-police-act-as-worship-place-looks-like-a-mosque.

[25] News Desk. (2020, December 21). ‘Shall not be forgiven’: PM’s aide vows to thoroughly probe Hindu temple attack. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2278148/shall-not-be-forgiven-pms-aide-vows-to-thoroughly-probe-hindu-temple-attack.

[26] Khan E. (2021, March 13). Hindu community pardons accused in Karak temple attack. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2289186/hindu-community-pardons-accused-in-karak-temple-attack.

[27] Khan, T. (2012, November 2). Religious harmony: Christian leaders pardon Mardan Church arsonists. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/459966/religious-harmony-christian-leaders-pardon-mardan-church-arsonists.

[28] Tanveer, R. (2012, January 16). Unfounded allegations: ‘Framed’ Christian moves court. The Express Tribune. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from http://tribune.com.pk/story/1026436/unfounded-allegations-framed-christian-moves-court/.

[29] Dawn. (2010, December 8). High-profile blasphemy cases in the last 63 years. Dawn. Retrieved April 21, 2021, from https://www.dawn.com/news/589587/high-profile-blasphemy-cases-in-the-last-63-years

[30] Asad, Malik. (2017, April 30). Blasphemy accused rejects allegations. Dawn. https://www.dawn.com/news/1330151/blasphemy-accused-rejects-allegations

[31] Malik, H. (2021, June 24). LHC points to several defects in blasphemy case. The Express Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2021, from https://tribune.com.pk/story/2306906/lhc-points-to-several-defects-in-blasphemy-case.

_____________________________________________

Download PDF